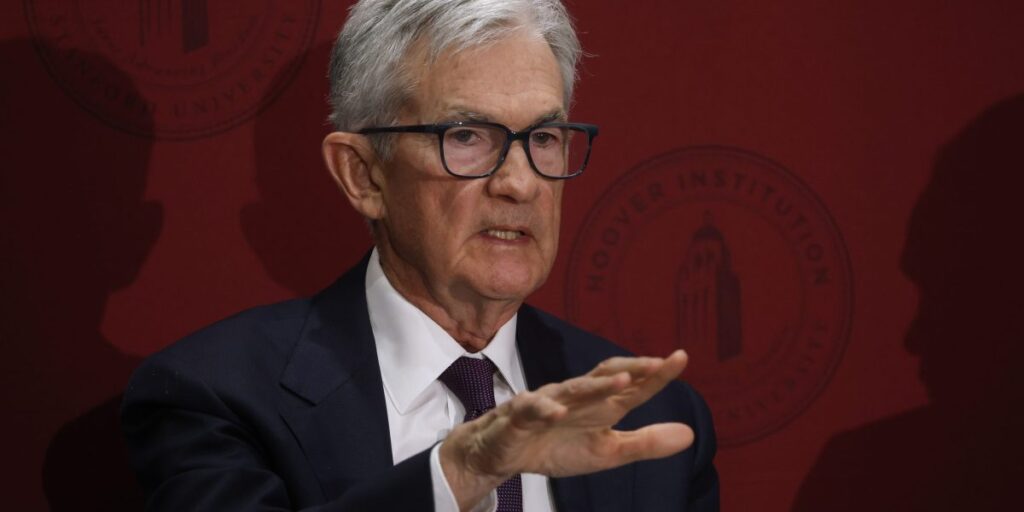

Trump’s pick for chairman isn’t enough to threaten Fed independence, says Bank of America—especially if Jerome Powell decides to stick around

“The question then becomes, will Powell leave as a governor?”

One of the major questions heading into 2026 is how deeply politics will be allowed to seep through the corridors of the Federal Reserve. This year, President Trump and his cabinet have lobbied for rate cuts and changes to monetary policy, which isn’t unheard of.

However, the White House has also taken more extreme measures: threatening to fire Fed Chair Jerome Powell while insulting him personally; attempting to remove other members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC); and visiting the central bank’s head office amid a tussle over renovation costs.

So looking ahead, analysts are already wondering what a Trump-nominated Fed chair will mean for the central bank’s independence. As UBS chief economist Paul Donovan highlighted in a note to clients earlier this week, a chair overly sympathetic to the views of the White House may draw “parallels” with a partnership between President Nixon and Fed Chair Arthur Burns in the 1970s—which ended in disaster.

“Burns ultimately faced rebellion within the ranks of the Fed, and the Fed has been showing more independence of spirit in its voting patterns on policy of late, so one should be cautious of reading too much into the actions of a single individual at the Fed,” Donovan added.

This was a caveat echoed by Bank of America’s senior U.S. economist, Aditya Bhave, in a briefing with media yesterday. Responding to a question from Fortune about risks to the Fed’s independence under a new chair, Bhave said the issue “almost depends more on what happens with the broader composition of the committee, rather than just the Fed chair.”

He explained: “So we know there’s gonna be a new Fed chair; we know that they’re probably gonna take Stephen Miran’s seat on the board. So in that sense, the leaning of the board from just inserting that person in and taking Miran out doesn’t really change that much, assuming they have a similar policy leaning to Miran.

“The question then becomes, will Powell leave as a governor?”

Miran was Trump’s chair at the Council of Economic Advisers before replacing Adriana Kugler on the Federal Open Market Committee following her resignation earlier this year. His is expected to be a temporary appointment, serving out Kugler’s term expiring next month.

And while the spot of Fed chair will be vacated by Powell in May 2026, his term as a Fed governor does not end until January 2028—meaning he could break with tradition and stay on at the Fed for a few more years, likely to the chagrin of the Oval Office.

“[Powell] has been very noncommittal about that,” added Bhave. “There’s very little historical precedent for a chair sticking around as governor. It hasn’t happened, I believe, in the last 75 years, but he hasn’t said he’s going to leave.”

Powell has been a staunch defender of Fed independence in the face of a barrage of criticism from the White House. He was firm in that he wouldn’t leave his position if the Oval Office requested it, and added that it wouldn’t be legal for an administration to make any such attempt.

“Our independence is a matter of law,” he noted to Bloomberg this summer. “Generally speaking, Fed independence is very widely understood and supported in Washington [and] in Congress, where it really matters. The point is we can make our decisions, and we will only make our decisions, based on our best thinking, based on our best analysis of the data, about what is the way to achieve our dual mandate goals … as to best serve the American people.”

Wider composition of the FOMC

Last month Raphael Bostic, president and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, confirmed he would be retiring at the end of his term in February 2026, representing another hole in the FOMC that Trump could fill with a dovish economist.

And there’s also the question of governor Lisa Cook, whom Trump tried to oust from the committee, and who will hear her case against the action in a Supreme Court hearing in January. The White House will be hoping that the legal process will fall in its favor, thus presenting a further opportunity for another appointment of its choosing.

“I think those questions are much more important if you’re thinking about a wholesale shift in thinking at the Fed than just who the next chair is going to be,” Bhave added. “If you take this committee—that is so hesitant to allow Powell to even do the next 25 basis points of cuts—for our estimates, there’s about eight of the 12 regional Fed presidents who don’t want to do that cut, either very explicitly or they somewhat would prefer to not do it. If you take this committee and you put them up against a Fed chair that says, ‘You know what, I want to go to 0.25%,’ I just don’t think that chair can make a lot of progress in that scenario.”