What CEOs say about AI and what they mean about layoffs and job cuts: Goldman Sachs peels the onion

“Companies that have discussed AI in the context of their workforce have cut their job openings more sharply this year,” economist Ronnie Walker found.

New economic analysis by Goldman Sachs reveals a bifurcated picture of artificial intelligence’s impact on the workforce, finding that while the technology’s role in current layoffs remains modest and unproven across the broader economy, companies focusing on AI in their workforce discussions have sharply curtailed their job openings this year.

The findings, drawn from an analysis of Q3 corporate earnings commentary and results by senior economist Ronnie Walker, were drawn from management commentary and results across nearly all the S&P 500. It showed that a relationship between overall labor market outcomes and AI exposure at the economy-wide level has yet to be established. But it also showed something else.

“While we still do not find a relationship between labor market outcomes and AI exposure at the economy-wide level,” Walker wrote, “we find that companies that have discussed AI in the context of their workforce have cut their job openings more sharply this year.” Indeed, Walker wrote that most components of Goldman’s layoff tracker “increased notably” in recent months.

While a minority of the layoffs discussed during third-quarter earnings were attributed to AI, the AI-related share increased notably through 2025, growing to just above 15% in the quarter. But more broadly, he highlighted that the companies discussing AI in the context of their workforce or layoffs “indeed appear to be pulling back disproportionately on hiring.” Walker highlighted the public release of ChatGPT in November 2022 as a recent marker of the rapid growth in AI focus, indicating that management teams are increasingly viewing AI not just as a tool for efficiency but as a core component of their future human capital strategy, leading to preemptive cuts in new roles.

Softer labor market backdrop

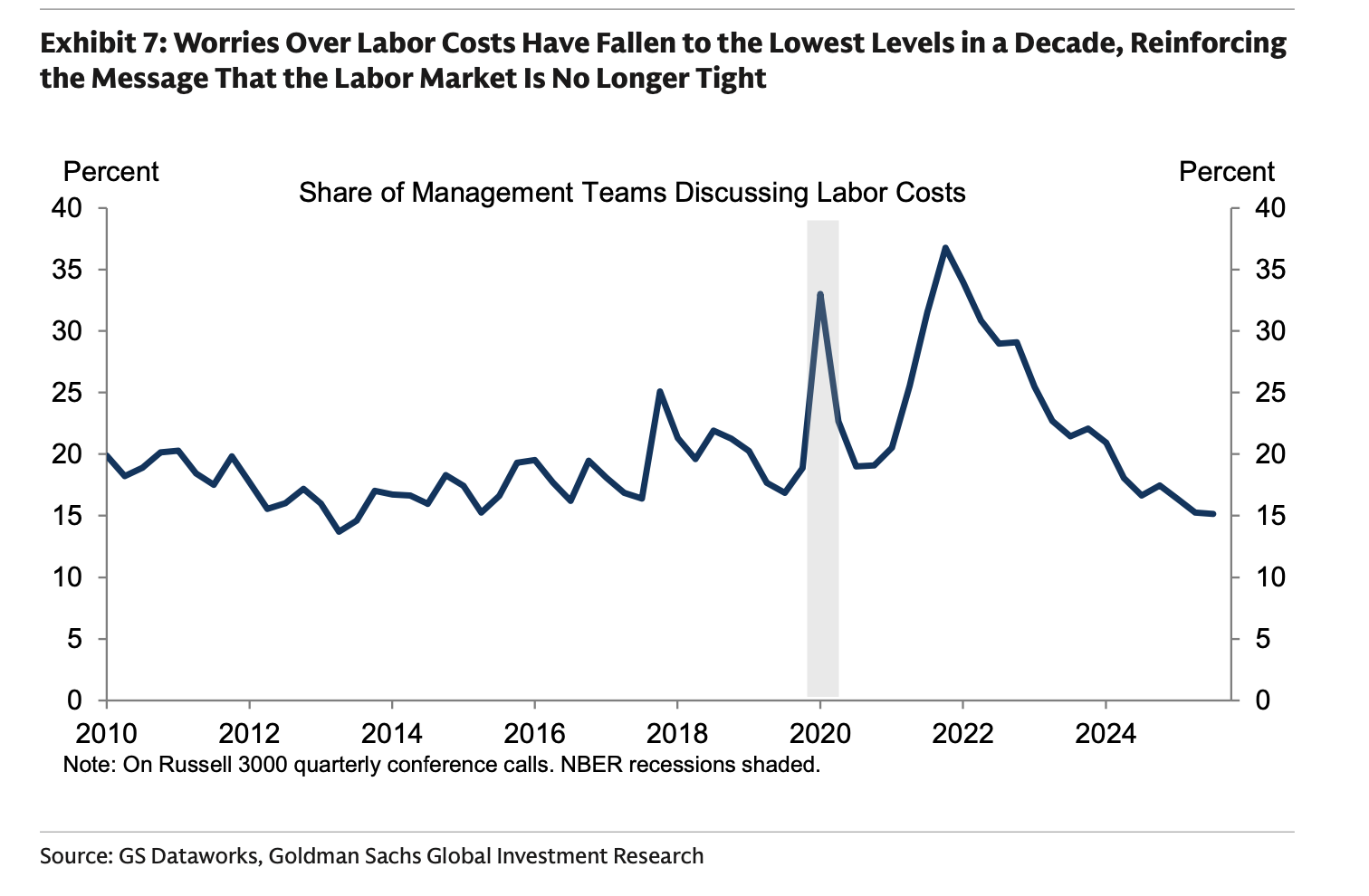

These AI-related hiring cuts occur amid a broader easing in the U.S. labor market. Company commentary confirmed that job growth remains tepid, and the labor market is softer than it was immediately prior to the pandemic. This increased “slack” has led to reduced concerns about compensation. Mentions of wages and labor costs in earnings calls have fallen to the “lower end of the pre-pandemic range,” reinforcing the message that executives are not worried about wages growing out of control anymore.

In other words, although Walker didn’t use these terms, the “Great Resignation,” when workers had significant leverage over employers, is retreating rapidly into the rearview mirror. This new era of fewer roles being advertised and a reluctance to hire has been termed, among other things, the “job-hugging” phase of the 2020s. Walker’s piece agrees with a previous analysis by his Goldman colleagues David Mericle and Pierfrancesco Mei, who argued in October that “jobless growth” may become a new normal feature of the post-pandemic economy.

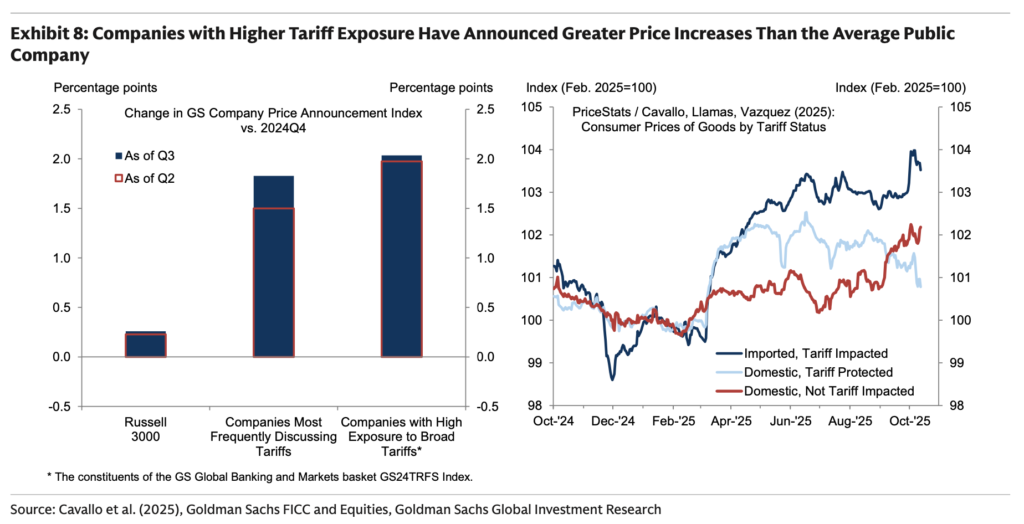

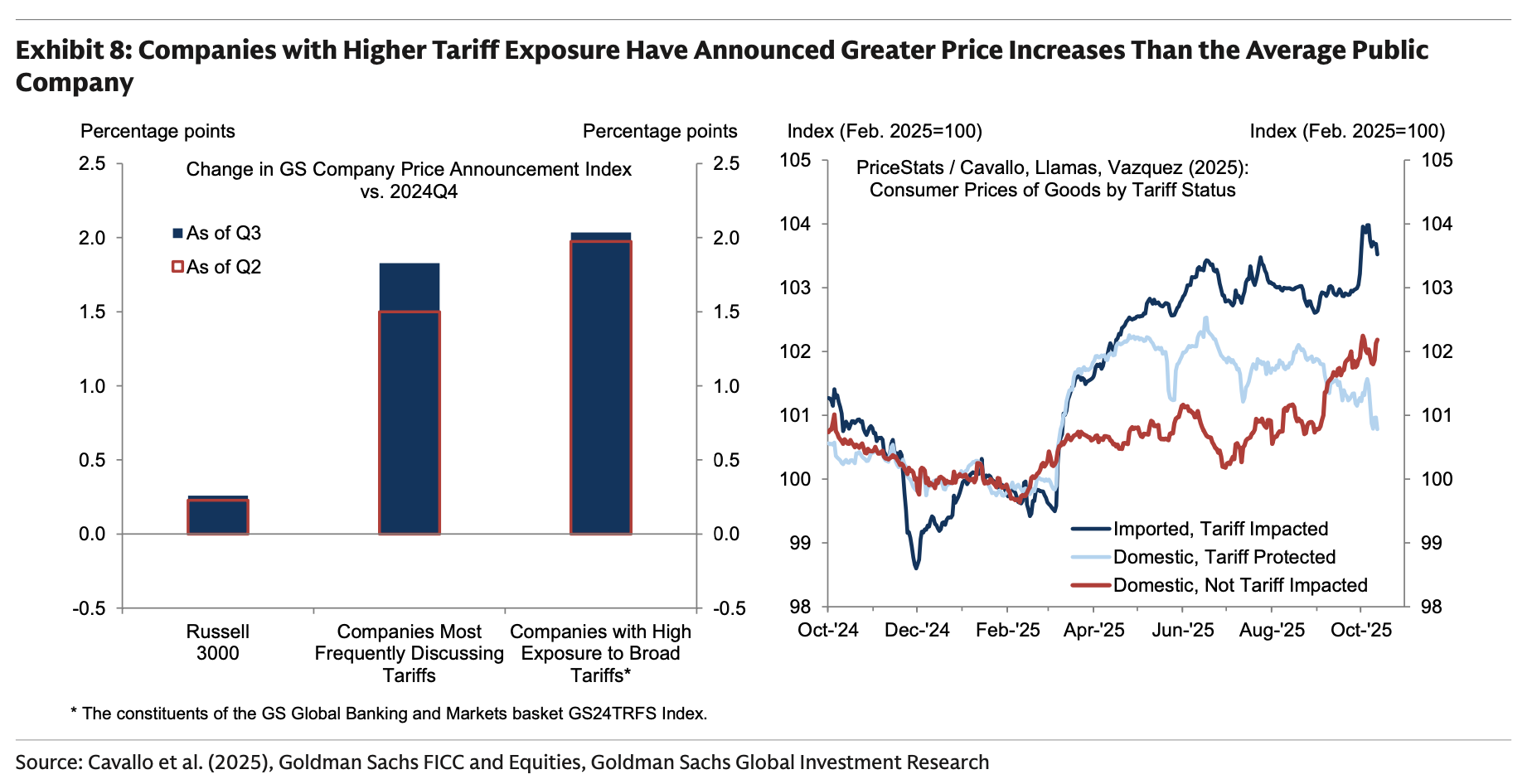

Further illustrating the cautious economic environment, companies facing persistent cost pressures, such as those with high tariff exposure, also sharply reduced their job openings this year. Walker found that the companies that most frequently discussed tariffs had “disproportionately cut job openings this year.” Some companies noted that they planned to mitigate costs by “hiring less, reducing headcount, or pursuing productivity-enhancing initiatives (such as investing in AI solutions).”

Q3 corporate context

Overall, Walker’s analysis found that corporate America is doing better than America itself, in terms of results. The largest companies demonstrated continued revenue strength, with real revenues (excluding energy) rising 4.1% year over year. This growth contrasts with the more “potential-like” 2.2% year-over-year growth in real GDP, a gap attributed partly to the greater international sales exposure of S&P 500 firms and the large weight of rapidly growing information technology companies.

Elsewhere, Walker found a “bifurcated” outlook, as his research agreed with many economists’ arguments that the U.S. has a “K-shaped economy,” where consumer spending is strong overall, but concerns about lower-income health abound. Walker agreed, writing that his team found that “the healthy aggregate trends mask divergences between companies that face lower- and higher-income consumers.” Sentiment around the consumer turned negative on earnings calls for retailers whose stores are generally located in lower-income zip codes, Walker found, with their same-store sales only growing 0.2% on average, as opposed to 2.5% for companies exposed to middle- and higher-income zip codes. This underperformance is expected to continue for the low-end consumer into 2026, Walker wrote, reflecting tepid job growth and pressure from benefit cuts.

Walker’s analysis agrees with anecdotal commentary from companies such as Delta and American Express, which rely on upper-middle-class consumers driving ever stronger results. And Federal Reserve governor Chris Waller told CNBC in early October that he was seeing the same bifurcation. Waller told CNBC’s Steve Liesman that high-income shoppers are “price-insensitive” and easily absorb tariff-related price hikes, with CEOs relating to him a roughly 40% pass-through at the upper end of the market. Waller called it a “two-tier” effect, with the lower half of the income distribution increasingly squeezed. If they see price hikes from tariffs, he added, CEOs are telling him they will just “walk out the door.”