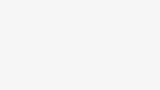

Transplant pioneer Sir Terence English dies at 93

Tributes are paid to the renowned surgeon who carried out the UK’s first successful heart transplant.

Rachael McMenemyand

Louise Parry

Sir Terence English

Sir Terence EnglishA pioneering surgeon who carried out the first successful heart transplant in the UK has died aged 93.

Sir Terence English had to fight for the right to carry out the surgery at Papworth Hospital in Cambridge in 1979, after resistance from the public and the government.

The operation that paved the way to future transplants took place in August that year on 52-year-old Keith Castle, who lived for more than five years afterwards.

Sir Terence’s family said he died on Sunday at his home in Iffley in Oxford, six days after having a stroke.

Sir Terence was born in South Africa in October 1932.

He studied mining engineering at Witwatersrand University in Johannesburg before deciding to switch to medicine, at Guy’s Hospital in London.

He married Ann in 1963 and they had four children – Katherine, Arthur, Mary and William.

William said his father often attributed his success to Ann, allowing him to focus on work and still enjoy family life.

“He felt a real sense of debt and gratitude to our mum, because the support she gave him and the home allowed him to have the career he did.”

His daughter Mary said the family were “immensely proud” of him and his work.

English family

English familySir Terence struggled to get government support for the procedure.

Speaking to the BBC in 2019, he said: “Before [Keith Castle’s] operation I’d been met with tremendous criticism about heart transplantation, including a letter from the Department for Health at the end of 1978 saying there would be no funding and the moratorium on heart transplantation would be continuing.

“I thought ‘damn that’ and managed to get approval from the Cambridge Area Health Authority – and we went ahead.”

In 1968, a heart transplant had been carried out by a team of 18 doctors and nurses led by another South African-born surgeon, Donald Ross, at the National Heart Hospital in Marylebone, London.

The patient, 45-year-old Frederick West, died 46 days after receiving the organ.

In January 1979, a transplant carried out by Sir Terence did not succeed.

While he was retrieving the donor heart, the recipient had a cardiac arrest.

He was quickly resuscitated and the subsequent operation went well, but the patient never recovered proper consciousness and died 17 days later.

Seven months later, he had one more chance to prove heart transplants could be life saving.

PA Media

PA MediaKeith Castle a builder from London, needed a new heart and despite being “not the best candidate” – he was a smoker with peripheral vascular disease and a duodenal ulcer – Sir Terence believed the transplant would work.

Heading into the operating theatre, Sir Terence reflected how he felt under immense pressure to succeed.

“I very much had my back to the wall,” he said.

Mr Castle lived for more than five years post-transplant and paved the way for the future of heart transplants at Papworth and in the UK.

“Looking back, having read bits back, the resistance to it [the heart transplant] was quite well founded, but he proved them wrong,” William said.

He said his father’s “conviction in own belief” was impressive but that he always said it was a team effort.

“And he always celebrated the team at Papworth. It was the team that was important,” he added.

Royal Papworth credited Sir Terence with helping it achieve an international reputation for heart transplantation and, later, heart-lung and lung transplants.

In 1991, he was knighted for his contributions to surgery and medicine.

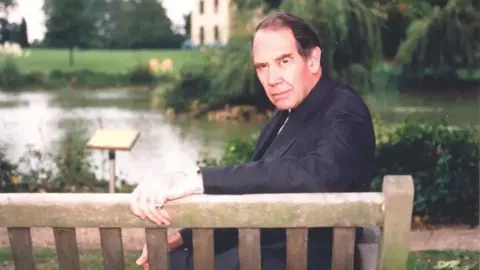

Sir Terence retired in the mid-1990s and moved to Oxford.

Royal Papworth

Royal PapworthAfter retiring, Sir Terence had several “encore careers”, his children said.

He served as President of the British Medical Association and took on charity work.

He was a trustee of IDEALS (International Disaster & Emergency Aid with Long Term Support) and was founding patron of Primary Trauma Care.

Both offer relief in areas affected by global conflict.

“He was a noted humanitarian who devoted his services to surgical support for doctors in Pakistan and Gaza over the years,” Mary said.

“Dad was able to take his lessons and learning to all parts of the world. He had an enduring appetite for work and to use his time in a meaningful way,” she added.

He also contributed to the debate about assisted dying through his work with Dignity in Dying, his family said.

Sir Terence was also a retired master of St Catharine’s College in Cambridge and honorary fellow of Worcester College Oxford.

English family

English familyHis family also remember a man who encouraged them to find their own passions and who showed immense care towards family, friends and patients over the years.

William said while his father was “committed to work”, he also had an “amazing capacity for friendship and a capacity to make connections with people”.

On his 93rd birthday, William said his father received an email from a patient he fitted with a heart valve 50 years ago, thanking him for his life.

“It said ‘I don’t know if you remember me but I think of you ever day’.”

“Dad replied saying ‘happy birthday to your heart valve’ – and that’s his enduring legacy.”

William, who works in intensive care medicine, said he also sees his father’s transplant legacy in his own patients.

“Organ donation is amazing, it revolutionises people’s lives. That ripple effect when you look at one person receiving a donor organ.”

Royal Papworth

Royal PapworthOutside of his work, Sir Terrence developed a love of classic cars, worldwide travel and an appreciation for the natural world.

He took part in car rallies, once driving from London to Cape Town.

“He did engineering first, so he was always interested in cars.”

“He bought a land cruiser he handed it down the family, he thought it was a very important family heirloom to pass down,” William said.

English family

English familyA history of heart transplants

- The world’s first human-to-human heart transplant was carried out on Louis Washkansky in Cape Town on 3 December 1967, led by South African surgeon Christiaan Barnard. Mr Washkansky, 54, died of pneumonia 18 days later

- The first heart transplant in the UK, on 3 May 1968 was performed by surgeon Donald Ross. The recipient, Fred West, 45, survived for 45 days

- A spate of heart transplants in 1968 and 1969 with short survival rates led to a UK moratorium on the procedure

- Sir Terence English carried out the first heart transplant at Papworth in January 1979. The patient survived for 17 days

- In August 1979, Keith Castle became the first recipient to be discharged from hospital in the UK, living for more than five years